After viewing the exhibition Eric Fischl: Rift Raft at the Skarstedt Gallery in New York a few months ago, I pondered the artist’s extensive use of the female nude in this, his most recent series of works. While nudes have been ubiquitous in Fischl’s paintings from the early psycho-sexual suburban narratives of the early 1980s to the less overtly allegorical, more formally oriented beach scenes produced in recent years, the new works offer a twist on his exploitation of the female nude as content. These paintings represent a continuation of his Art Fair Series begun in 2013. Having been invited to an art fair to give a talk, he was appalled and fascinated by the attendees and their responses (or lack thereof) to the art on view. He then visited a few art fairs with his digital camera in hand, later collaging images from these photographs together in Photoshop and using them as the basis for this series of large-scale paintings.

In the tellingly titled The Disconnect, two men (or is it the same man at different moments in time?) disregard Fischl’s own Girl with Doll (1987). One of the men is preoccupied with his camera, while the other walks away. Keith Haring’s dog barks in this man’s ear, as if to call him to attention, while a Lichtenstein brushstroke sculpture seems poised to devour the other man. It would appear that Fischl’s intention was to point out the disconnect between the work of artists like himself who endeavor to make a statement about the frailty and absurdity of the human condition (as evidenced by his painting of the naked, somber-faced adolescent girl and her oddly clinging moose), and the indifferent art fair attendee. In She Says, “Can I Help You?” He Says, “It Can’t Be Helped.”, yet another version of the same man takes a cellphone photo of a painting of a voluptuous female nude, which suggests a tame (less exaggerated in form) version of a work by Lisa Yuskavage. (Yuskavage paints hyper-sexualized images of women at ease in their nudity in psychologically charged works that pose a challenge to conventions of porn and voyeurism.) The man’s photographing of this work is seemingly critiqued (his lascivious nature unalterable, as suggested by the title) by the furrow-browed glare of the female nude in the painting below.

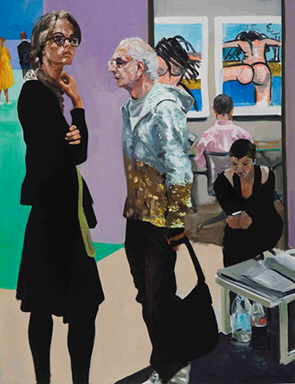

What Doesn’t…Go Away…Miss? shows both gallerists and fairgoers set against a backdrop consisting of two images of Carol Dunham’s lusty, exuberantly sexual, in-your-face female nudes. All manage to ignore the Dunhams, including the man in the pink shirt in whose face the images appear. In the left foreground, a woman, who is as shielded by her black clothing as Dunham’s figures are exposed in their nudity, stands in a self-protective gesture, looking out of the painting and away from the speaking man standing before her. Fischl opposes the repressed nature of the female fairgoer’s sexuality with that of Carol Dunham’s bathers who exult in their eroticism.

This reading of the transparency of the work’s content in no way seeks to imply that the painting is simplistic or lacking in subtlety and brilliance. It is rich in color, gorgeously painted and extremely complex spatially with a multiplicity of motifs held in perfect balance. The economical handling of the soda bottles in the lower right is killer and the rendering of the black-on-black clothing typically seen at art fairs is wonderfully exploited here and in other works to produce eloquent silhouettes that also serve to punch holes in the picture space. The figures are large scale and the vantage point is such that their space appears to be an extension of our own, fostering intimacy and immediacy. Body language is closely observed and plays an essential part in the storytelling.

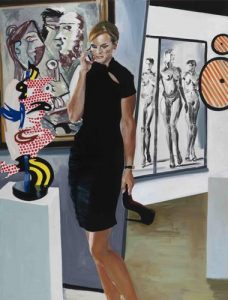

In Watch, a young female gallery assistant stands in yet another, self-protective pose, defending herself against the overt nudity of Tom Wesselmann’s Great American Nude #57 (1964) and the Yuskavage-like grisaille. In Her, a stately and elegant woman, again dressed in black, her high-heel shoe held in her hand, is speaking on her cellphone. Self-absorbed, her demeanor contrasts with that of Roy Lichtenstein’s flirtatious Barcelona Head (1992), which stands on the pedestal before her. On the wall behind is a Vanessa Beecroft-like image of nude women in high-heels (Beecroft’s performances, documented by photographs, often feature large groups on display, their subject being the male gaze). To the left behind the woman is Picasso’s Homme et femme I (1971), in which one of the women’s breasts and a form that suggests the man’s erect penis are prominent. To the right are two fragments of another Lichtenstein sculpture, Galatea (1990), one representing the mythological figure’s breast and the other her belly (complete with belly button), in an echo of the grisaille Beercroft nudes. Fischl’s subject would again seem to be the repression of sexuality in our culture in contrast with art’s embrace of eroticism as vital to human experience. The artist may also have sought to give expression to his own desires, playing Pygmalion to his contemporary fairgoer’s Galatea.

The mythic is addressed on far grander scale and with a high seriousness that contrasts with the other works on view in the diptych that provided the exhibition with its name, Rift Raft. This monumental painting presents an update on Fischl’s large-scale diptych, A Visit to/A Visit From/The Island (1983), in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art. In the earlier painting, the left-hand panel shows a beach scene in bright, sun-drenched colors in which an adolescent boy in a white t-shirt stands awkwardly biting his nails in the midst of nude white vacationers who frolic in the turquoise waters of an upscale resort. In the predominantly gray, storm-tossed beachscape on the right-hand panel, a black woman garbed in white gesticulates and cries out in a tragic scene in which black figures, presumably the island’s natives, frantically come to the aid of others, many of whom lie motionless.

The right-hand panel of Rift Raft also offers a scene of turmoil–asylum seeking refugees, among them an old woman and a young boy, struggling in the water, being giving assistance and carried to safety. The left-hand panel again presents a tableau from an art fair, but this one is imagined because it shows four female nudes intermingled among five resting fairgoers. It is as if nudes from Fischl’s earlier beach paintings stepped off their appointed canvases into the space of this picture. None of the figures on the left-hand panel are aware of the chaos taking place to the right (the rift raft, as it were), some being on their cellphones, while others stare off into space. One of the nudes, however, turns her head to look at what appears to be an abstract painting by Christopher Wool. Yet another nude, her arms raised to her forehead, looks out of Fischl’s painting to the viewer standing before it with what appears to be a troubled and critical gaze.

The image of one of Andy Warhol’s Car Crash paintings from his Death and Disaster Series positioned directly behind her may provide one of the keys to Fischl’s intentions, as Warhol is understood to have employed mass media images to which people had become desensitized through their repetition. The reports of the Syrian refugee crisis in the daily news leave Americans, who are not directly affected, largely unmoved, the crisis becoming something of an abstraction, as expressed perhaps by the chaotic swirling rhythms and organic forms of the Wool. Fischl’s integration of the sort of nudes that have long served as muses for his art among the fairgoers that populate his Art Fair Series, whose actions he has playfully mocked and parodied, appears self-accusatory. It stands as a confession of his hedonistic self-absorption and a commentary on the inattention and inaction of others in the face of everyday horrors. In Rift Raft, it is truth stripped bare.

With thanks to Dr. Enrique Mallen, Director and Editor of the Online Picasso Project, Sam Houston State University, for helping me identify Homme et femme I, Mougins 2-28, 1971.