Among the recent initiatives of the Arshile Gorky Foundation have been two endeavors that have shed light on Gorky’s personal and artistic legacy. One is the exhibition Ardent Nature: Arshile Gorky Landscapes, 1943-47, recently on view at Hauser + Wirth on 69th Street, New York. It offered a breathtaking array of works produced by the artist at the height of his powers, the time when he liberated himself from his earlier sources to create an art–a world–wholly his own. Curated by Saskia Spender, one of the artist’s granddaughters and head of the Foundation, it consisted of 30 paintings and drawing drawn from museums and private collections. The other is the 2011 documentary film Without Gorky, written and directed by his other granddaughter, Cosima Spender, which was on view at H + W in as small upstairs gallery. The film, which is also available on Netflix, focuses on his family life. While at times a docu-drama filled with information extraneous to an understanding of the artist and his work, the film does much to illuminate the fecund span of the works in the exhibition, which for Gorky was the best and then the very worst of times.

During the summer of 1943, Gorky, who had previously devoted himself to the study of Old Master and Modernist painting, turned to the study of nature. Leaving the New York City home and studio he shared with his wife and daughter for the spaciousness and ease of Crooked Run Farm, a property in the Virginia countryside owned by his wife’s family, he made hundreds of drawings of plants, trees, cows in the fields, insects, and more. Taking cues from Surrealism’s biomorphic forms, automatic drawing, and belief that the source of art resides in the unconscious, lessons he gleaned in large part from his friend, the painter Roberto Matta, he used these drawings to evolve a language of organic, multivalent forms that conveyed the inner world of his psyche. The immersion in nature and calm of this period roused in him memories of his early childhood with his parents in the foothills and on the shores of Lake Van in Turkish Armenia. The titles and verdant lushness of the paintings Scent of Apricots in the Fields and Apple Orchard evoke these happy times. Although Gorky took pains during his lifetime to hide the family’s subsequent history, it has long been known that after this brief idyll, his father left for America and Gorky, his mother, and sister moved from the countryside into town. Shortly thereafter, they were caught in the horrors of the Armenian Genocide, his mother dying of starvation. Gorky and his sister immigrated to America.

By the spring of 1944, Gorky and his young family were living full time in the countryside, first at Crooked Run Farm, then in Roxbury, Connecticut, and shortly after the birth of his second daughter, in Sherman, Connecticut, where tragedy again befell him. In January 1946, a fire in his studio destroyed much of his work. He was then diagnosed with rectal cancer, which forced the use of a colostomy bag. During this same period, Gorky’s career was flourishing: he was exhibiting regularly at the Julien Levy Gallery and had begun to receive from the gallery a modest monthly stipend, alleviating his financial worries; he was included in 14 Americans at MoMA and other important group exhibitions; and he was being celebrated by the Surrealists as one of their own while being identified as a leading figure in the new American art soon to be dubbed “Abstract Expressionism.” Gorky, however, was in pain, depressed, and suffering humiliation at his failing body.

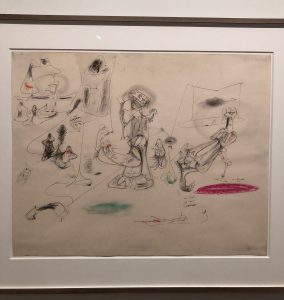

Included in the exhibition are numerous paintings and drawings of the Pastoral Series of 1946-47. These works are of a shared composition and imagery, but are remarkably divergent in execution, handling, and mood. In the Theme for Pastoral (1946) drawing, a series of hybrid forms–humanoid and botanical–are distributed across a field, the smaller elements to the left indicating a recession into depth. Elements rendered in the round through contour drawing and shading are phallic, anal, muscular, and visceral. Thin, wiry lines suggest nerves stretched to their breaking points. Hardly “pastoral,” the landscape is filled with tension and offers an abstracted version of a Boschian Hell, one that gives expression to the nightmare of Gorky’s loss of bodily functions.

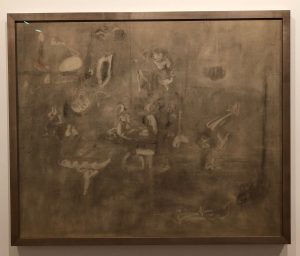

The subdued and even meltingly romantic Gray Drawing for Pastoral (ca.1946-1947) presents a “ghost version” of the same motif. A monochromatic work executed in charcoal, many of whose forms are rendered by erasure, the hybrid figures appear immersed in dense smoke or fog, a Leonardesque sfumato. A lighter-than-air, almost cartoonish version is found in the painting Pastoral (1947), whose composition is dominated by a bright yellow plane. The forms set within holes in this surface are loosley drawn and thinly painted, the artist improvising with the motif while in a seemingly lighthearted mood.

As was discovered in 2000 when it was sent for reframing, however, hidden behind this painting was another on the theme of an entirely different state of mind. Here the surface is brown, connoting smeared excrement. The forms are of a dominant peach (read: flesh-colored) tonality with blood red and puss yellow touches and abundant drips. Although it has been said that this canvas was covered over because Gorky had run out of stretchers, so doubled up, and then forgot it was there, it seems more likely that Gorky felt this work too revealing of self to see light of day.

In June 1948, an automobile accident left Gorky with a broken neck and collarbone and immobilized his painting arm. His wife left him, taking the two children with her. On July 21, 1948, Gorky committed suicide by hanging, leaving the chalked note, “Goodbye My Loveds.”

The documentary Without Gorky consists largely of interviews with Gorky’s “Loveds”–his wife and their daughters, Maro and Natasha. As the daughters were very young at the time of his suicide and remember little of their father, it is his widow, Agnes “Mougouch” Gorky, whose memories and stories are responsible for painting the family portrait. “Mougouch” is an Armenian endearment that means “little mighty one,” although Mougouch portrays herself as having been a passive, unformed young woman dominated by a husband almost twenty years her senior. She explains that as a mother of two in her mid-twenties, she was traumatized by Gorky’s anger and depression at the calamities that had befallen him, which drove her to seek solace in the arms of Roberto Matta. Knowledge of their affair contributed to Gorky’s taking his own life.

The 88-year-old Mougouch who appears in the film is indeed a “mighty one.” She is an indomitable, highly critical and opinionated, entirely riveting figure, whose daughters treat her with ambivalence. After Gorky’s death, she deposited them–at ages 3 and 5–in a Swiss boarding school, so as to go off with Matta. (Although not mentioned in the film, she went on to have two more husbands and two other daughters; she died in 2013.) During the course of the film, as they learn more about the history of their parents’ marriage, Maro and Natasha come to better terms with her.

At the end of the film, the daughters make a pilgrimage to the shores of Lake Van in Eastern Turkey, where their father resided as a young child. In the space of the landscape that lived on in his memories and fortified his art, they attain a sense of closure and a connection to the legendary figure they hardly knew.